“but since we’re all gonna die,” or, the myth of the morning routine

on lifestyle content and the debt of the artist to “the real.”

“[E]liminated from the realist speech act as a signified of denotation, the ‘real’ returns to it as a signified of connotation; for just when these details are reputed to denote the real directly, all that they do—without saying so—is signify it; Flaubert’s barometer, Michelet’s little door finally say nothing but this: we are the real; it is the category of ‘the real’ (and not its contingent contents) which is then signified; in other words, the very absence of the signified, to the advantage of the referent alone, becomes the very signifier of realism: the reality effect is produced, the basis of that unavowed verisimilitude which forms the aesthetic of all the standard works of modernity.” — Roland Barthes, “The Reality Effect,” in The Rustle of Language (1986), trans. Richard Howard, p. 148.

Just before January 19, believing TikTok would soon be permanently banned from U.S. territory, content creators took to the platform one final time to recite their own last rites. The trend was to sample a line from Family Guy—“But since we’re all gonna die, there’s one last secret I feel like I have to share with you”—then reveal a lie they had told to get famous. Someone on TikTok had faked having gone to high school with Jenny Ortega by stealing a friend’s yearbook, she admitted, “for the clout.” Twinfluencers Niki and Gabi, who now have nine million subscribers on YouTube, had rented, one of them revealed (to the tune of 213,000 likes on TikTok), a second house for filming content for $4,000 a month and paid another influencer to take pictures in Los Angeles to conceal the fact that both houses, real and staged, were in Pennsylvania. Bonus lie: they would buy their own “Christmas presents” in advance, so theirs would be the first “haul” video to go live each year at 8 a.m. on December 25. When asked in her comments about her “routine” videos, which regularly squished two hours of activities in twenty minutes of timestamps, Aspyn Ovard, who has two million followers, said bluntly: “I thought we all knew that those videos were not real … I thought we all knew that those videos were just for entertainment.”

I learned about the Family Guy gambit—which, of course, lost some of its redemptive flavor when the clock struck twelve on January 20 and TikTok came back online—from the YouTuber Nicole Rafiee, whose Chronically Online Girl Explains series has helped me remain reasonably informed on the internet “lore” since adopting the pop culture diet of a monk (I deleted my Instagram). The video essay is titled “sooo influencers are admitting they are lying lol.” Rafiee’s thesis is that it is harmful for influencers to produce the illusion of wealth, beauty, and superhuman productivity at the expense of their young viewers’ self-esteem. Her generation didn’t have, Rafiee tells us, an Emma Chamberlain, who, although now only relatable to those of us who have multimillion-dollar mansions in Los Angeles and a brand ambassadorship for Lancôme, was once upon a time renowned for her channel’s “realness.” She was funny, she was skinny in a kiddish way and had pimples on her forehead, she ate weird and burped on camera and didn’t always brush her hair. She still did hype-y challenges and bought mountains of clothing and drove around the suburbs in an enormous car, but the way that she did it, to quote Cate Matthews in TIME, “shook up YouTube’s unofficial style guide.” Matthews calls her aesthetic adjacent to “normcore.” She did that funny zooming thing with her phone.

Rafiee’s video concludes with an infographic on media literacy (including, crucially, an exhortation to “reflect on financial motives for content”) and a cutesy outro insisting that “you can absolutely be an honest content creator and be fun and cool and sexy and hot and like whimsical and have a sparkle in your eye and be honest in the content that you’re making to your audience” (subtext, thereafter explicited: “it’s me”). That’s one conclusion to reach. But as I am not a YouTuber and thus have no skin in the game of making honest fun cool sexy hot and like whimsical content, the point of the Family Guy thing seemed to me to be something else altogether.

I was struck, in both the “exposing” content and Rafiee’s commentary, by the fixation on something everyone presumes really exists behind the artifice: the real. To her, the lesson we all should learn from this trend is to be more “honest” on the internet. The twins should have filmed from their real bedrooms and shown their followers the gifts their loved ones really bought them; Aspyn Ovard should have filmed what she really does in the mornings, how often she really gets up and goes to the gym. Then we all could watch their videos and come away with reasonable expectations about how big our bedrooms should be, how many Christmas gifts we should expect to receive, how many activities we can reasonably hope to accomplish between waking up and going to school or our jobs—jobs we have to work, but which successful influencers, and here’s the important part, don’t.

The premise of the form of the lifestyle video is, let’s face it, that the viewer can hope to replicate the influencer’s patterns of living without becoming a professional influencer themselves. But those hopes, or rather their falseness, are the chips in the influence game. The sense of un-reality, of the better-than-the-real—the sense that what is represented is greater and more glamorous than what currently exists in our own lives, and yet that what is represented is possible to attain—is the very currency of our aspirations, which themselves invent the possibility of influence. If the job of the influencer is in the end to perform, that is, to simulate, a lifestyle that only becomes possible the moment the lifestyle becomes the job itself, what’s really exposed, with the stage-house and the fabricated morning timestamps, is the stratum of unreality at which the value of “content” is generated: the fiction that we, too, can live a life we never will, unless we enter the economy of lifestyle content creation ourselves.

This is what makes Aspyn Ovard’s refrain sound like bullshit: the slippage from “influence” to “entertainment,” as though she had no sense that the job of the lifestyle content creator is to set expectations and—and here is where the money flows—create corresponding desires. Otherwise, why would we watch what she, or anyone like her, posts online? In one of the exposing videos, the twins repeat Aspyn Ovard’s refrain. “The reaction,” Niki tells viewers, to her “exposing” TikTok series—because yes, her last confession before the fictional ByteDance crackdown unfurled into a multi-part “exposing series” in which she exposed “secrets” of her formerly popular twin channel over get-ready-with-me TikToks, with which she was building an influencing empire of her own—“was not expected. I thought a lot of the things that were fake or staged were obvious, but obviously they were not.” Gabi chimes in: “There’s many things that you guys are surprised about that I was just shook weren’t obvious.”

When the Aspyn Ovards and the Niki and Gabi’s of the world feign (I think this is the appropriate verb—you may disagree) surprise that creator and viewer had not tacitly agreed to take the “content” as “entertainment,” and therefore release it from the constraints of “honesty” and “realism,” they efface the actual unspoken contract at play, that is, that what is represented is something the viewer should desire for themselves. What Barthes might, should he permit the application of his literary concept to the “low” form of the lifestyle video, call the “reality effect” of the form is really a carefully constructed simulation of what is plausible, not a representation of “real things” themselves. For Barthes, what the concrete details of a work of fiction signify are not their “signified” (a real barometer, a real door; a real bedroom, a real breakfast), but the status of the “real” itself. And so, Ovard’s timestamps, Niki and Gabi’s stage-house signify that their lives, that we, are in the realm of the “real,” which invites—in fact, invents the possibility of—influence, that is to say, something to imitate.

The demystification trend, far from a final confession that it was always a constructed “effect,” in the end generated its own genre of content, no less artificial than that which its progenitors pretended to unmask. After the success of Niki’s TikTok series, she and Gabi both took to YouTube to film a “TRUTH OR DRINK: Exposing the Niki & Gabi Channel” video this March over a handle of Tito’s. In the intro, Gabi frames the video as a “long-form” version of her sister’s TikTok series, in which the pair will answer the questions people asked in the “exposing series” comments—or take a shot. The “exposing” trend, then, for Niki and Gabi no differently than for anyone else, only introduces another set of fictions into the fold of “the brand.” “Clearly we’re trying to change the trajectory for like the next decade of our content,” Niki and Gabi explain. “We just want it to be so fucking real.” (In the end, we learn the Tito’s bottle was filled with water all along.)

“Realness,” like the trend of “exposing” oneself, becomes thereby another gimmick, another turn of the “influence” screw. By rebranding oneself as “real,” an influencer can control the flow of information to their viewers to draw their attention away from what remains concealed. In her more recent videos—in the post–Emma Chamberlain era, since it has become trendy to be “real” online—Aspyn Ovard has, for example, started styling her video titles like text messages, using chatty slang like “lore” and “era” and inviting her users to get to know her with “q&a’s,” and presenting an “authentic” image with “realistic updates” and videos with “vulnerable” titles like “im not okay.” Consider Emma Chamberlain herself, whose most “real” vlogs involved, TIME tells us, upwards of thirty hours of editing apiece. Does that mean she’s dishonest? Or simply a master of the form—that is, of the game?

Suppose the lifestyle video is an art. Who knows? Maybe it is. Supposing the lifestyle video is an art, we can ask ourselves why it should be subject to a different set of rules than other disciplines, all of which have undergone at some point or other a crisis, or a questioning, of the practitioner’s debt to “the real.” In painting, for example: the old tradition of academic realism which, although often styled to the ideal, concealed that idealization by the same gesture with which it imitated “real” life: a finger, a collarbone, the curvature of the toe. And the rise in the nineteenth century of the “moderns”—“impressionists,” “expressionists”—who accepted the canvas for what it was (a surface), called our attention to the act itself of painting, and by so doing made visual culture more “honest” than ever before.

These sorts of painters, the “modern” painters, despite abandoning the realistic conventions of their forefathers, tended to excite scandal for representing real subjects they should not have. Take the French painter Edouard Manet’s Olympia, for instance. With its high contrasts, suppressed middle-tones, and loose brushstrokes, the work calls attention to its status as a painted surface. In this way, it is less “realistic” than, say, The Birth of Venus by Alexandre Cabanel, the nude par excellence of Second Empire France, painted that same year. And yet Olympia scandalized the Parisian public in 1863 for its frank depiction of a nude sex worker without pretext of myth, which, until that moment, had been the veil through which the viewing public compelled painters to offer the nude subject. Some “fiction” was required—Biblical, Orientalist, antique—to authorize the representation of what was otherwise taboo. Moreover, where a Cabanel would fuse ideal elements from different models’ bodies to produce the image of an idealized woman, Manet painted his model, Victorine Meurent, as she was. “Euphemism,” writes Pierre Bourdieu in his lectures on Manet, “is what one does when it comes to naming the unnamable” (p. 57). Manet’s painting broke that spell. And so, Emile Zola’s often-quoted line: “When our artists give us Venuses, they lie. Edouard Manet asked himself, why lie, why not tell the truth; he made us know Olympia, this woman of our time” (Manet : Étude biographique et critique, p. 36).

The scandal of Olympia calls attention to the point at which commentary on the form of lifestyle content has stunted, even among those seeking to remedy the “dishonesty” of the past. It shows us the extent to which the discourse has been arrested by a collective fixation on a quality of “realness” that is itself part of a play of mystifications and ideals. The content creators have not, that is, admitted to the fact that they are painting on a surface.

But the above reading of Olympia is, by now, commonplace in art history scholarship; I can’t take credit for it. Personally, I think the painting is too often, in this scholarship and elsewhere, misread as simply a nude, rather what I think it really is: a portrait of two women. The worker, the Black woman in the right of the canvas, is equally a subject of the canvas as her employer, the infamous white femme entretenue, who herself exists in a labor relation—or a potential one—with the viewers, ourselves. What the painting represents, I think, then, is the exchange of money itself: between the domestic worker and the sex worker, and between the sex worker and the client, with the large bouquet of flowers, which we are to understand is a gift from one such customer, standing in for the transubstantiation of love into transaction. This transubstantiation is, itself, I think, the essential taboo that Olympia displays. Viewers’ persistent neglect of the relations of work represented within the canvas reflects what is at play in the charade of “lifestyle” content: the concealment of labor itself.

Like lifestyle content, “high art” also participates in the production of desire. In the realm of “influence,” the gap between the real and the simulated is itself essential to this productive process. In the history of painting, this operation is, if more subtle, no less powerful. The French painter Paul Gauguin’s depictions of Tahiti, for example, are widely understood to have functioned as an engine of European tourism to French Polynesia throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries.

Gauguin’s style of representation was obviously “unrealistic”: he worked with saturated and unexpected colors, loose and geometric forms. But when Gauguin first exhibited his Tahitian paintings in Paris in 1893, he constructed a careful apparatus of credibility to position his paintings as “ethnographic.” “I was reborn; or rather, in me was reborn a pure and strong man,” he wrote in Noa Noa, his hybrid memoir of his time in Tahiti, published too late but intended to accompany the exhibition in 1893. “I was another man now, a savage, a Maorie [sic]” (p. 68). Charles Morice, who wrote the preface to the exhibition catalog which viewers would have read in the gallery at the time, asserted that Gauguin “made himself savage, he was naturalized Maorie [sic]—without ceasing to be himself—to be an artist.” The Tahitian painting’s pretense of credibility was Gauguin’s capacity to embody the experience of a Maohi (not “Maorie”) person and thereby express something true.

In Noa Noa, Gauguin describes encountering an island culture that had, in reality, been effaced by French colonialism and various flavors of Christian missionaries. To this extent, he admits that what he paints in, for example, Arearea from 1892, was not what he saw. He describes fleeing the colonial capital of Papeete for the countryside, where he married a thirteen-year-old-girl, Teha’amana, who, he tells us, told him the lost history of her people. “The Gods of long ago,” he writes, “are preserved in the memory of women” (p. 10). These Gods, represented in Arearea by the great stone idol in the background, he tells us, represented forces of nature—“a trait common to all primitive religions” (p. 123). In fact, Teha’amana’s “testimony” was a fabrication; the “primitive” theology Gauguin claimed to have discovered first-hand had actually been taken whole-cloth from the 1837 writings of the Belgian merchant Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout. Moerenhout had, in turn, taken down the testimonies of surviving local priests and fused them with a European imaginary of Greek antiquity transposed to the Oceanian mode. Western fictions, that is, structured Gauguin’s “Tahitian” oeuvre from the start; although Gauguin really did marry a child called Teha’amana, her “voice” in the text is merely a pretense.

In Orientalism, Edward Said suggests that European academics and artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries invented an imaginary cartography, “the Orient,” which they presented as the product of empirical observation; they thereby assembled the architecture of imperial ideology through which Europe naturalized its political domination over (real-world) territory abroad. For Said, Orientalism “shares with magic and mythology the autonomous, self-reinforcing character of a closed system, in which things are what they are because they are what they are, for once, for all time, for ontological reasons that no empirical material can shift or change” (Orientalism, p. 70). The invention of a link between what is essentially a “closed” and “autonomous” representation and the real is the final gesture in the construction of the colonial alibi. Gauguin’s particular version of Orientalism is the fiction of the primitive, by which tribal cultures are positioned backwards in time from European modernity, which widely served, as Dipesh Chakrabarty writes, to distance colonial subjects from the possibility of self-rule (Provincializing Europe, pp. 7-8).

Okay, so Arearea represents a myth, a powerful myth, a European myth, about the meanings of civilization and “primitivity,” rather than a historical mythology indigenous to Tahiti. The territory represented in Arearea is not in the end Tahiti but a figment of Gauguin’s imagination, in which Easter Island tikis, Marquesan ancestral figures, Egyptian pharaohs, and the Buddha fuse in the idol of a fictitious ritual, and in which the visual vocabularies of Peru, Japan, Iran, and Cambodia blend. If we know this about Arearea, why can’t we abandon its ethnographic pretensions and confront it as a representation of that process of simulation and mystification itself? Putting aside Gauguin’s insistence on the “realism” of his work, as Chakrabarty and Said have shown, the colonizer’s representations of the colonized redound in real ways upon the terrain of political life. We cannot, then, simply subtract a painting from the ideological context that gives it both meaning and power.

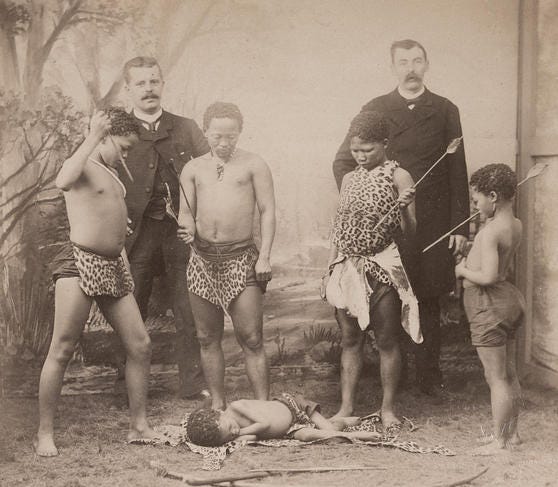

A few years before Gauguin exhibited Arearea in Paris, colonial subjects were transported to the city to be displayed in human zoos in the Jardin d’Acclimatation of the 1889 Colonial Exhibition, performing “native” habits of life in staged villages for European spectators. The influence of this Exhibition on Gauguin’s curiosity about “primitive” cultures is widely acknowledged. One of his more vicious reviewers, Georges Darien, made plain in L’Escarmouche in 1893 that the only context in which a “true Maorie [sic]” could arrive in Paris at the time would have been “at the Jardin d’Acclimatation”—that is, themselves on display.

The culture of human zoos, and the role of spectacle in the production of European fantasies of primitivism within them, are the subject of a piece of performance and, later, video art made by Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña in the 1990s. In The Couple in the Cage: Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West, Fusco, who is Cuban American, and Gómez-Peña, who is Mexican, pretended to be members of an “undiscovered Amerindian” tribe and traveled around Europe in a cage. The performances were filmed by Paula Heredia, and this film, The Couple in the Cage: Guatianaui Odyssey, revealed the European spectators to have been, all along, the true subjects of the piece. We, viewers of the video, witness the performance’s white viewing publics accepting the incarceration and exhibition of what they believe to be Indigenous people like animals in a zoo. In the end, what we have witnessed is not Fusco and Gómez-Peña, or their “Amerindian” avatars, but the operation of European fantasy and prejudice.

Why am I talking about this? Because I think the long arc from Gauguin’s initial exhibition, with its ethnographic pretensions, to Fusco and Gómez-Peña’s performance, tells us something about how forms of visual production, the play between the representation and the represented, can be brought into the folds of art itself. It helps us think about how the ideological subtext and political effects of imagination can be made themselves the subject of art, where “creators” call attention to the operations of their work on the realm of the “real.” To return to the lifestyle video, we can use the concept of the “myth,” which, as Roland Barthes writes, is a fiction chosen by history to “negate all situations of History” itself—that is to say, to present as natural or essential that which is in fact a historical process (Mythologies, p. 152, 182). This is also the way ideology works to legitimize the order of things as they are.

So, the lifestyle video. By unmasking the set of ideological operations by which the influencer simulates and thereby naturalizes the ideal life, which is a life (most often) of unending consumption, they would defang the mechanism by which their “content” can monetize, which is what makes their profession possible in the first place. The lifestyle video can only exist if viewers believe in the possibility of replicating what the influencer demonstrates; by removing “content” from the plane of real and placing it on the true level of “entertainment,” the influencer would abolish the supposedly traversable distance between what the viewer has and what the influencer displays—and by so doing, allow the viewer to abandon the project of traversing it, that is to say, of consuming more. That moniker, “entertainment,” ultimately obscures the extent to which the lifestyle video is really a personalized form of subliminal advertisement. The influencer can thus never actually bring us behind the façade because by so doing the lifestyle video essentially abolishes itself. As Niki says at the end of TRUTH OR DRINK: “The truth sets you free.”

“Beneath this mask, another mask; I will never end up removing all these faces.” — Claude Cahun, Aveux non avenus, 1928.